There are avoidable behaviours that contribute to these statistics such as speeding. Speeding is one of the most influential predictors of RTCs, with research [3] heavily supporting the notion that the higher the speed of vehicle, the greater the likelihood of serious injury or death if there is a collision.

In 2020, 202 people were killed in RTCs involving someone exceeding the speed limit, with a further 1,368 people seriously injured and 2,803 slightly injured [4]. In 2021, police recorded that travelling too fast or exceeding the speed limit was a contributory factor in 25% of fatal road crashes [5]. TRL wrote a report in 2000 investigating the impact of traffic speed on the frequency of road accidents, highlighting compelling evidence that in a range of road and traffic conditions, the frequency of accidents increases with the speed of traffic [6].

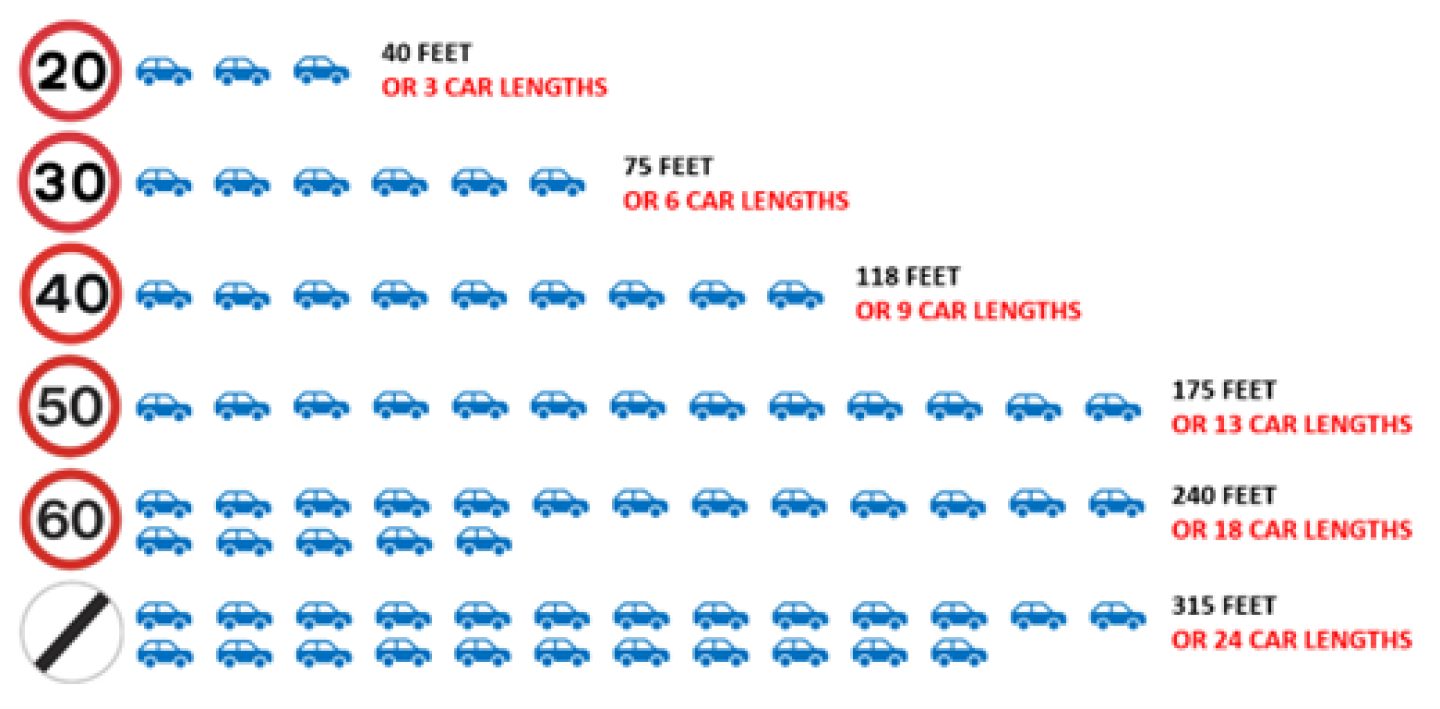

These statistics can be explained by simple physics – when a vehicle is travelling at high speeds, it requires more time and distance to come to a complete stop. The faster the speed, the longer the stopping distance, and the less time the driver has to react to any potential hazards. The figure below summarises the typical stopping distances at different speeds.

Stopping distances data from Enjuris [7]

People who drive for work are at higher risk of speeding and being involved in an RTC. A study found that company car drivers, on average, drive faster than other drivers [8]. This may be associated with several factors such as running late, hitting traffic, distracted driving and simply disobeying the law. Those who drive for work might also think their time is more precious that other road users. This is a huge concern for not only fleet managers, but the safety of other road users.

What can be done to tackle speeding?

There are various ways organisations can tackle speeding within their fleets, starting from an organisational cultural shift in the delivery and tone of safety messages. It is crucial for companies to display a consistent front when eliminating undesirable driving behaviours, like speeding.

From an evidence review conducted by TRL, it was found that there was no silver bullet for improving fleet safety, therefore a comprehensive approach should be taken, focusing on the weakest areas of fleet safety. This includes commitment and leadership from management, engagement for employees such as group discussions, a trusting relationship between managers and employees, and a clear and congruent implementation of an agreed safety strategy [9]. When delivering safety messages, things like grammar (e.g., using “we” instead of “you” helps foster a sense of collective responsibility), tone, frequency, and length all play an important role in the receptiveness of messages. Positive framings or being proactive can often be more effectively received than negative messages of punishment.

Alternative ways of encouraging safer driving behaviours comes from the use of behaviour-change techniques when using telematics data. Telematics systems play a pivotal role in enhancing work-related road safety, as it enables real-time monitoring and data-driven insights. When used correctly, telematics systems can address safety issues such as speeding while driving for work. A behaviour-change technique (BCT) is a theory-based method that helps an individual change their behaviour to realise a desired outcome. They are empirically supported techniques that can be used alone or in combination with others. In order to be effective, techniques need to be observable, replicable, irreducible, and a component of an intervention designed to change behaviour [10]. There are 93 BCTs that can be applied to interventions – but here are the top 6 most relevant techniques to tackle speeding behaviours. These techniques may be used independently, or in combination.

- Providing feedback on behaviour – providing drivers with feedback about their speeding habits has been shown to improve young drivers’ speed compliance [11].

- Non-specific incentive and reward – inform drivers that a reward will be given if there has been effort and/or progress in driving more safely (identified by a threshold criteria) [12].

- Review behaviour goal(s) – working with drivers to review their progress against their goal of not speeding: what they have mastered, how successful this has been, and do the goals need to be changed? [13]

- Problem-solving – working with drivers to help them identify the barriers that make it more difficult for them to change their behaviour, and what they can do to overcome these barriers [14].

- Information about consequences – telling drivers about how speeding can increase their chance of being in a collision [15].

- Anticipated regret – asking drivers to imagine how they will feel if they speed and crash, writing their car off and injuring themselves or other people, has been shown to influence offending drivers’ speeding behaviours [16].

The National Driver Offender Retraining Scheme run courses that drivers are offered instead of being prosecuted for speeding. The course contained various BCTs to change attitudes and norms, which in turn can act on intentions.

Attendees were asked to explore the things that make it difficult for them to drive within the speed limit, to consider a specific journey in which they are at risk of speeding, to complete an action plan that specifies what they will do differently before and during the journey to ensure they don’t speed, and to identify if they will need anybody’s help to do this. Before the end of the session, the attendees were asked to write down what would have to happen before they wished they’d changed something [17].

BCTs used:

- Problem-solving – reflecting on the barriers that make it more difficult to drive within the speed limit, and identifying what can be done to overcome those barriers;

- Action planning – identifying exactly what they will do to make sure they don’t speed on a specific journey;

- Social support – identifying somebody who can help them avoid speeding

- Anticipated regret – considering the situation (e.g., you drive into and killed something, such as an animal, or someone) that would lead them to regret not changing their behaviour.

Practical things fleet managers can encourage their drivers to do to prevent speeding:

- Obey traffic laws – make sure drivers are familiar with the speed limit in the area

Use cruise control – many cars have cruise control features that allow drivers to set a maximum speed - Stay focused – avoid distractions while driving, such as texting, talking on the phone, or eating, as these can cause drivers to lose focus and inadvertently speed

- Give enough time – plan routes and leave early, so drivers don’t feel rushed and tempted to speed to arrive at their destination on time

- Check speed regularly – keep an eye on the speedometer to make speed limited aren’t being exceeded

- Speak up when under pressure – ensure that work demands don’t make drivers feel that they have to break the law.

There is no doubt that inappropriate speed is one of the most serious road safety problems on Britain’s roads, causing death and injury to thousands of people each year. A cultural shift towards safer driving behaviour is not an overnight fix and there is no fast-track, but there are things that organisations and fleet managers can adopt to get closer to the root issue. Most importantly, help drivers to drive the safety agenda.

Annie Avis and Robert Lynam of TRL wrote this blog for Road Safety Week. Sign up to join the national conversation about speed.

TRL is a world leader in transport safety and has developed products and expert services that have been proven to analyse, minimise and prevent road collisions.

In support of Road Safety Week 2023, TRL experts are discussing speed-related road safety topics and considering how this can change make transport safe for everyone.

Find out more at trl.co.uk

Robert joined the Behavioural Sciences team at TRL after completing his postgraduate degree in Social Research from the University of Birmingham. He has been involved in work-related road safety projects and is currently helping to monitor and evaluate behaviour change interventions. His other interests lie in understanding attitudes and behaviours surrounding active travel and new mobility.

Annie is a member of the Behavioural Sciences team at TRL and holds a master’s degree in psychology, with a specific interest in social psychology, human performance and the mechanisms underlying behaviour change. Annie has worked on projects that have evaluated behaviour change courses to reduce speeding offences, assessed fleet drivers' attitudes towards dangerous driving behaviours, and investigated how nudges and feedback can be used to enhance driver safety.

- Driving for work: A strategic review of risks associated with cars and light vans and implications for policy and practice (2020)

- Driving at work: Managing work-related road safety

- Elvik, R., Vadeby, A., Hels, T., & Van Schagen, I. (2019). Updated estimates of the relationship between speed and road safety at the aggregate and individual levels. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 123, 114-122.; See also Brake: Speed & Injury. How impact speed affects injury.

- https://www.rospa.com/road-safety/advice/drivers/speeding

- https://www.brake.org.uk/get-involved/take-action/mybrake/knowledge-centre/uk-road-safety

- https://trl.co.uk/uploads/trl/documents/TRL421.pdf

- https://www.enjuris.com/blog/questions/correlation-between-speed-and-car-accident-injuries/

- RAC’s Report on Motoring (2014)

- Naevestad T, Hesjevoll, I. & Phillips, R. (2018). How can we improve safety culture in transport organisations? A review of interventions, effects and influencing factors. Transport Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 54, 28-46

- Michie S, van Stralen MM and West R (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Sci, 6 (42). doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

- Molloy O, Molesworth B, Williamson A and Senserrick T (2023). Improving young drivers’ speed compliance through a single dose of feedback. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 95, 228-238. doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2023.04.006

- Scott-Parker B, Watson B and King MJ (2009). Understanding the psychosocial factors influencing the risky behaviour of young drivers. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 12 (6), 470-482. doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2009.08.003

- Brewster S, Elliott M and Kelly S (2015). Evidence that implementation intentions reduce drivers’ speeding behavior: testing a new intervention to change driver behavior. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 74, 229-242. doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2014.11.006

- Flyan F and Stradling S (2014). Behavioural Change Techniques used in road safety interventions for young people. European Review of Applied Psychology, 64 (3), 123-129. doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2014.02.003

- Ibid.

- Elliot MA and Thompson JA (2010). The social cognitive determinants of offending drivers’ speeding behaviour. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 42 (6), 1595-1605. doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2010.03.018

- Fylan F (2017). Using Behaviour Change Techniques: Guidance for the road safety community. RAC Foundation: London.